Around the time when Justin Trudeau announced his candidacy for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, I remember seeing an article that claimed that he had a good chance because he had “spent time in the trenches” during the previous federal election campaign.

Around the time when Justin Trudeau announced his candidacy for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, I remember seeing an article that claimed that he had a good chance because he had “spent time in the trenches” during the previous federal election campaign.Justin Trudeau in the trenches? Had he been embedded with Canadian forces in Afghanistan? How come I had not heard about it? I continued reading. Of course, Justin Trudeau has spent no more “time in the trenches” than I have. The writer was referring to his door-to-door campaigning in Montreal. Now, I realize that Montreal can get pretty cold, and that people aren’t always friendly to unsolicited visitors. But this hardly amounts to “time in the trenches.”

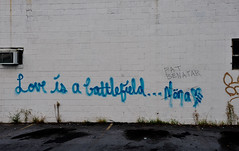

Military metaphors and the language of violent conflict are a ready source of clichés for journalists and bloggers. We have the “war on the car,” the “war on Christmas,” “patent wars” between Apple and Samsung, and even an alleged “war against boys” in the education system. It is commonplace to describe any dispute as a “battleground.” We often hear of the necessity to “open a new front” in some conflict. (This usually amounts to something like filing a motion in court.) Last week Bill Daly, deputy commissioner of the National Hockey League, made the ridiculous remark that the NHL’s demand to limit player contract lengths to five years would be “the hill we will die on.” Please. I understand that professional hockey is important to many people in this country, and if I were one of those people, I would certainly be very frustrated right now. But holding fast to your position in a negotiation is not remotely like a heroic martyrdom in battle, no matter how much money or whatever “principles” are at stake.

The appeal of exaggerated language is not hard to fathom. Leaders speak of “rallying the troops” and “fighting the good fight” because doing so is motivational. People need to feel that their actions matter, the consequences are significant, and that the conflict they’re engaged in is important. Journalists present rather banal disputes and legal contests as “battles” in an effort to gain and hold our attention. But not every conflict is worthy of a “fight to the death.” The stakes are not always high. Even in a zero-sum type of conflict where compromise is impossible and only one side can prevail, the consequences of both winning and losing can be less momentous than the participants believe. The passage of time has a way of making both wins and loses less important than they seem at present.

The overuse of military metaphors is tiresome, but that isn’t the most important reason to resist it. This form of language inflation has consequences. If a conflict is a “battle” or a “war,” then it follows that one’s opponents are “the enemy” (and perhaps “evil” as well.) If one side is the “victor” (who presumably is entitled to the spoils), then the “vanquished” side is shamed or humiliated. If the other party in a dispute is not just someone you happen to disagree with, or someone whose interests are opposed to yours, but an “enemy,” then that makes compromise much more challenging. It makes hearing their position more difficult, and opportunities for joint problem solving and mutual gain are likely to be overlooked.

Considering every disagreement, whether it is a civic dispute, a political difference, or a legal contest, as a “war” or “battle” is probably bad for your mental health, and maybe even detrimental to the public good. Violent conflicts with life-and-death consequences are taking place now in Afghanistan, Syria, and Congo, to mention only a few. Let’s not trivialize the experiences of people there by exaggerating the importance and severity of our own conflicts.