Bill 168 has been law now for just over two years, and we haven’t yet seen many decisions interpreting and applying the legislation. A recent ruling by arbitrator David Starkman is of interest to labour and employment lawyers and HR professionals because it provides some guidance about Bill 168’s scope and application. Below I briefly summarize and discuss this very interesting case.

Background: In 2010 the Peterborough Regional Health Centre, faced with the need to reduce costs, took a decision to replace some of the Registered Nurses (RNs) in the Hemodialysis Unit with Registered Practical Nurses (RPNs). RPNs have less education than RNs, earn less money, and have narrower scope of practice. The Health Centre Management planned a 6-week orientation period for the RPNs when they would be mentored by the RNs. However many of the RNs were unhappy about the introduction of RPNs, which would result in the layoff of RNs, and which they feared would compromise patient care. Several RNs refused to volunteer to mentor their new colleagues.

Incidentally (or maybe, not so incidentally), the RNs’ concerns were later shown to be valid. An

Independent Assessment Committee found that the hospital failed to plan adequately for the staffing changes, and failed to evaluate whether the changes affected patient care.

Allegations: Although there seemed to be a great deal of tension and bad feelings in the unit when the RPNs started, one of the RNs in particular was particularly hostile. (I will call her Sally.) She engaged in non-verbal behaviour designed to make the RPNs uncomfortable, including rolling her eyes at them, staring and flapping her hands as they walked by her work area, refusing to make eye contact, and on one occasion, walking directly toward an RPN and making contact with her shoulder. Another RPN reported that, while she was washing her hands at a sink, Sally came behind her, tried to pull her hair in to a ponytail, and made remarks to the effect that, patients do not want hair in the way.

The Employer’s Response: Reading the testimony presented to the arbitrator, there were clearly many problems on the unit. Several of the RPNs quit and spoke of an atmosphere of bullying. Morale was very low. After a number of complaints abut Sally, the employer met with her to discuss their concerns. Sally did not acknowledge any wrongdoing. When her inappropriate behaviour continued, Sally was put on paid leave while the employer undertook an investigation. The result of the investigation was that Sally was found to have engaged in a pattern of intimidation and harassment and was terminated for just cause. Sally grieved both the decision to place her on leave and the firing.

The Arbitrator’s Decision: Mr. Starkman found that the employer had just cause to discipline Sally and to put her on paid leave pending an investigation. However, they did not have just cause to terminate her employment. Although the employer had discussed their concerns with Sally she was

never formally disciplined. While Starkman acknowledged that Sally’s conduct was very subtle and therefore difficult to evaluate and discipline, he held that the principle of progressive discipline nonetheless applied, and that termination was too severe a penalty.

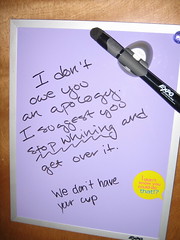

However, he also found that Sally’s conduct, her refusal to acknowledge that her behaviour was inappropriate, and her failure to apologize, meant that she should not be returned to the unit. Instead, he directed that Sally be paid damages in lieu of reinstatement.

(Just an aside – some of you may be wondering, “Can Sally really not have understood that her behaviour was inappropriate? I’m afraid that this is entirely possible. For one thing, her co-workers were very reluctant to confront her about her actions. And trying to understand it from Sally’s perspective, she likely saw herself as a strong advocate for patient care, not as someone who made the workplace a nightmare for others!)

Lessons for Employees: If you disagree with management’s decisions, don’t take it out on others. Even if you have a valid point, the organization’s

code of conduct still applies. And if management raises concerns about your behaviour, take it seriously. If you are on the receiving end of inappropriate behaviour, speak up – either raise a concern directly with the offending party or if that is not possible, speak to management or HR.

Lessons for Employers: Several of the people who spoke with the arbitrator reported that Sally’s behaviour in the workplace had been a source of tension for a long time. When employers fail to deal directly with inappropriate behaviour, it rarely corrects itself on its own. Inaction and delay result in greater costs down the line. (See my post on the

costs of workplace strife for more information.)

Lessons for Everyone: Eye-rolling? Flapping one’s hands? Is this really intimidation and harassment, such that discipline is appropriate? The answer is yes. It is clear from the testimony that the RPNs felt bullied, harassed, and unsupported in their work. As Mr. Starkman wrote in his decision, Sally’s actions were “extremely subtle, and in that sense were extremely insidious. Bullying and harassment can consist of a single incident, or a series of repeated incidents both of which can have great impact upon the victim of the behaviour.”

Note: I offer investigations of complaints related to workplace harassment, bullying, sexual harassment, and other matters covered under bill 168. See my website for more information, or contact me directly to discuss the situation in your workplace.

One of the most popular posts on this blog is one I wrote more than two years ago, about asking for an apology. At least once a day, someone somewhere searches for the phrase “asking for an apology” or “how to ask for an apology” and finds my post.

One of the most popular posts on this blog is one I wrote more than two years ago, about asking for an apology. At least once a day, someone somewhere searches for the phrase “asking for an apology” or “how to ask for an apology” and finds my post.

You may have heard that Tuesday night’s performance by the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall was abruptly halted because of a stubbornly loud and persistent cell phone. The orchestra was playing the final movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, considered by some to be one of the most emotionally rich and sublime pieces of music ever written. Towards the end, at the worst possible moment, the insistent plinking of the iphone “marimba” ringtone completely shattered the atmosphere. Alan Gilbert, the conductor of the Philharmonic, actually stopped the performance and glared at the offender until he managed to silence the phone. (You can read an amusing account of the evening

You may have heard that Tuesday night’s performance by the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall was abruptly halted because of a stubbornly loud and persistent cell phone. The orchestra was playing the final movement of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, considered by some to be one of the most emotionally rich and sublime pieces of music ever written. Towards the end, at the worst possible moment, the insistent plinking of the iphone “marimba” ringtone completely shattered the atmosphere. Alan Gilbert, the conductor of the Philharmonic, actually stopped the performance and glared at the offender until he managed to silence the phone. (You can read an amusing account of the evening