A friend recently told me that she hadn’t seen much of her husband lately. At first I wondered if their relationship was on the rocks. Instead it turns out that the new head of his division insists on 12-hour days from all the senior people. Now, I’ve put in my share of 12-hour days. When I had my first jobs teaching philosophy in university I had to work very hard and sometimes kept long hours. But I liked the work and I didn’t mind that much. I understood that many people have to keep even longer hours at jobs that they don’t find so rewarding, and I realized that companies sometimes have “crunch” times when they must make excessive demands of their staff.

A friend recently told me that she hadn’t seen much of her husband lately. At first I wondered if their relationship was on the rocks. Instead it turns out that the new head of his division insists on 12-hour days from all the senior people. Now, I’ve put in my share of 12-hour days. When I had my first jobs teaching philosophy in university I had to work very hard and sometimes kept long hours. But I liked the work and I didn’t mind that much. I understood that many people have to keep even longer hours at jobs that they don’t find so rewarding, and I realized that companies sometimes have “crunch” times when they must make excessive demands of their staff.My friend’s husband – I’ll just call him “Simon” – does not work for a struggling start-up, and he doesn’t have the kind of job (like, say, in a law firm) where there is a direct relationship between the hours he works and the amount of money he brings in. He works for a major company in a profitable industry. And while the industry does provide a socially useful function, it isn’t as if he’s about to find a cure for AIDS or devise a way to stop global warming. Simon is good at what he does and well compensated for it. I suppose that if the long hours bothered him that much he might decide to seek work elsewhere.

So while I understand that 12-hour (and longer) days might sometimes be necessary, I find it a bit troubling that a 12-hour day is the expected norm. What will they do when a crunch really does arrive – provide sleeping bags and a catered breakfast so that employees don’t even have to go home? I imagine that Simon’s boss has made his demand in order to establish a certain culture in the company. Any ambitious man or woman a little lower down in the hierarchy need only to consider the hours of the senior people to know what they must do to get ahead.

The boss’s ukase strikes me as bad management for a number of reasons. Demanding that employees put in twelve-hour days is not the same as demanding that they do 12 hours worth of work. The jobs that are affected are knowledge-based, requiring creativity and advanced problem-solving skills. It is not the sort of work that you can do effectively for long hours many days at a stretch. This means that some of those compelled to put in a 12-hour day are doing their usual seven or eight hours of work and stretching it out to take up 12 hours. What a waste of time and human potential! It probably also means that some of the twelve hours are taken up by non-productive, time-wasting exercises. I can imagine endless boring and irrelevant meetings and long back-logs of unread emails that one should never have been sent in the first place. When you factor in the stress of long days, resentment at the fact that employees can no longer make time for the gym or other interests, and the added strain on their families, you end up with a pretty unhappy (not to say dysfunctional) workplace.

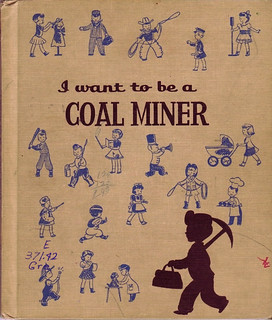

It is puzzling to me that a company would hire people they believe to be smart and capable, and then treat them like coal miners who must spend a certain number of hours chipping away underground. Let’s set aside the question of whether this amounts to bad management. Are such demands unethical? There are reasons to think so. The company Simon works for is in an industry in which there is a certain amount of hand-wringing at the under-representation of women. I’m willing to bet that every major company in the industry has a policy to address this concern. Insisting that employees regularly spend twelve hours at the office if they want to get ahead is especially hard on women, who often have non-negotiable family obligations. A corporate culture of overwork is just one more barrier to their success.

This is absolutely a problem for the gender gap. It was telling to me when one of my law professors last semester said, "Yup, so it's all up to you [future female lawyers] to make improvements in private practice cuz I've done my time and I'm not going back."

ReplyDeleteWhat's interesting to me in the evolution of corporate culture is the cooptation that's happening in the "work is fun" movement, as demonstrated by Google, where kitchens and free food are stocked all the time, nap stations are available, games, etc. The culture it panders to, though, is the single male. When I first saw the Googleplex, I was enthralled and impressed and the labour rights implications followed afterwards through talking about it with people and reflecting on my own values. When talking about it with a friend at a start-up in the region, he said he'd never want to work there because "[He's] a grown-ass man" with a family. I don't think we need to have an antagonistic relationship with work to justify working reasonable hours, and I agree that some women don't have negotiable family obligations. What I think is interesting is that corporations are side-stepping human rights codes by constructing workplace geographies and cultures by presenting the illusion of "choosing to work late". Recently, a law school friend justified eating at the firm's restaurant by working longer hours, not the other way around. What this says to me is that my generation is not as entitled as they seem to be and that some people see through the ruse and achieve a balance while others do not.

As I chart my own career path (yet again), I am considering criminal law, where I expect to be woken up in the middle of the night by clients who need me and whose constitutional rights (including life and liberty) I am paid to defend. The way I look at it is more through the analogy of medicine: professionals on call to help us with ailments that would otherwise kill us. Do we then carve out an exception for those professionals? How do we delineate between "important" jobs and will that not create cognitive dissonance that could also poison a workplace?

Thanks Vanessa! You make an excellent point about the "work is fun" culture. Sure, work can be fun and also very personally rewarding. But so can a lot of other activities, and these usually require time away from work. I'm a firm believer that time away from work helps energize and inspire us, and this in turn makes us better at the work we do.

ReplyDelete